The case of Comité Interprofessionnel du Vin de Champagne v Aldi Süd Dienstleistungs-GmbH & Co. OHG dealt with the sale of a sorbet by Aldi, manufactured by a third-party. The sorbet was called 'Champagner Sorbet', consisting of 12% champagne among the various ingredients used. The name 'Champagne' has long been registered as a PDO (PDO-FR-A1359), protected by CIVIC, the claimant, which is the association of champagne producers. They objected to the name 'Champagner Sorbet' and took Aldi to court to prevent the sale of the sorbet in Germany. The matter ultimately ended up at the CJEU.

The first question asked whether "…Article 118m(2)(a)(ii) of Regulation No 1234/2007 and Article 103(2)(a)(ii) of Regulation No 1308/2013… are to be interpreted as meaning that the scope of those provisions covers a situation where a PDO, such as ‘Champagne’, is used as part of the name under which a foodstuff is sold, such as ‘Champagner Sorbet’, and where that foodstuff does not correspond to the product specifications for that PDO but contains an ingredient which does correspond to those specifications". Both provisions prevent the use of the PDO in commercial use, including sale of goods, if they don't comply with the PDO's specifications and attempt to exploit its reputation.

Per the CJEU, the protection afforded aims to ensure the high quality of goods in the EU, including as an ingredient in other goods, and similarly the use of the PDO has to apply to goods that only meet the specifications set. This means that the Articles above "…are applicable to the commercial use of a PDO, such as ‘Champagne’, as part of the name of a foodstuff, such as ‘Champagner Sorbet’, containing an ingredient which corresponds to the product specifications of the PDO".

The second question enquired whether "…[the Articles] are to be interpreted as meaning that the use of a PDO as part of the name under which is sold a foodstuff that does not correspond to the product specifications for that PDO but contains an ingredient that does correspond to those specifications, such as ‘Champagner Sorbet’, constitutes exploitation of the reputation of a PDO… where the name of the foodstuff corresponds to the name by which the relevant public usually refers to that foodstuff and the ingredient has been added in sufficient quantity to give the foodstuff one of its essential characteristics". Put in a different way; can you use the name Champagne to describe goods that have champagne as an ingredient, so long as it is used in sufficient quantity.

As discussed by the CJEU, the reputation of a PDO derives from the guaranteed quality the specifications offer the consumer, i.e. that what they buy is always consistent. The reputation has to be protected from third-parties seeking to benefit from it by using the name without the quality demanded. The same applies to marketing activities where a PDO is used in conjunction with a product to sell goods not conforming to the specifications. The Court therefore settled that the use of the name champagne could potentially be unduly exploiting the PDO when used in the name 'Champagner Sorbet', conveying an air of luxury and prestige.

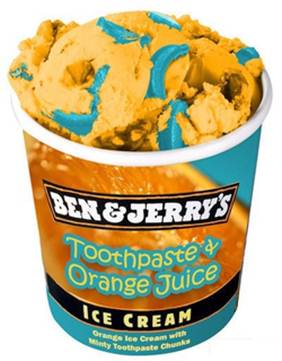

|

| Not all cold treats are received as well |

The CJEU determined that "…the use of a PDO as part of the name under which is sold a foodstuff that does not correspond to the product specifications for that PDO but contains an ingredient which does correspond to those specifications cannot be regarded, in itself, as an unfair use". [48-]

The Court then considered the test of whether a 'sufficient quantity' of the specification corresponding goods has been used as an ingredient. They did note that there would be no minimum percentage, and those goods using them as an ingredient would take unfair advantage of the PDO if that ingredient does not confer on that foodstuff one of its essential characteristics. How this is determined is, according to the Court "…establishing that that foodstuff has... the aroma or taste imparted by that ingredient".

The CJEU summarised its conclusion as "…the use of a PDO as part of the name under which is sold a foodstuff that does not correspond to the product specifications for that PDO but contains an ingredient that does correspond to those specifications… constitutes exploitation of the reputation of a PDO… if that foodstuff does not have, as one of its essential characteristics, a taste attributable primarily to the presence of that ingredient in the composition of the foodstuff".

They then moved onto the third question, which asked whether the use of a PDO in the name of goods containing a corresponding good as its ingredient would amount to misuse, imitation or evocation within the meaning of the above Articles. Following their answer to the first and second questions, the Court quickly dismissed this as the use of the PDO to claim openly a gustatory quality connected with goods does not amount to misuse, imitation or evocation.

Finally, the Court took on the fourth question, which asked whether the Articles above are to be interpreted as applying only to false or misleading indications that the goods are of the same quality and origin as the PDO.

The CJEU swiftly set out that the Articles apply to both to false or misleading indications as to the geographical origin of the product concerned and to its nature or essential qualities. Should the sorbet not have had champagne as an essential characteristic the provider would have made a false or misleading indication within the meaning of the Articles.

The case is very interesting, particularly as it opens the door for producers to use PDOs and similar marks in conjunction with goods that incorporate them as an essential characteristic, i.e. a prominent ingredient. This writer could think of Roquefort ice cream or even Parma hamburgers, as potential uses of this new capability; however, the incorporation of PDO goods might be trickier than the case may indicate.

No comments:

Post a Comment

All comments will be moderated before publication. Any messages that contain, among other things, irrelevant content, advertising, spam, or are otherwise against good taste, will not be published.

Please keep all messages to the topic and as relevant as possible.

Should your message have been removed in error or you would want to complain about a removal, please email any complaints to jani.ihalainen(at)gmail.com.