As diligent readers of this blog have probably noted, the last 12 months have been vary favorable to those who are inclined to law reforms, especially in the

field of copyright. This writer, for one, enjoys the rapid changes being introduced, and has awaited the next step of the reform process, which

was leaked not long ago; the European Union

Single Digital Market strategy. The strategy encompasses much more than just IP within it in attempts to combat the issues plaguing the internal digital market, and this post shall endeavor to touch upon the most relevant parts, divided by the "pillars" they're under.

Pillar I - Better Access For Consumers and Businesses to Online Goods and Services Across Europe

Along with the introduction of changes to e-commerce regulation, delivery systems and VAT within the European Digital Economy, the strategy also proposes some key changes into the landscape in which copyright resides.

Geo-blocking has, and will be, a contentious issue, especially in this global world where not all consumers are created equal in their access to media. The strategy states that:

"[b]y limiting consumer opportunities and choice, geo-blocking is a significant cause of consumer dissatisfaction and of fragmentation of the Internal Market", and while arguably true to a certain extent, the statement does not reflect the commercial nature of geo-blocking. Often it is used to ensure either the locking in of content to regions, or to secure proper negotiations for wider, more lucrative licensing agreements (whether you agree with this notion or not is an entirely different matter). The strategy discusses 'unjustified' geo-blocking, but as to what amounts to an unjustified use remains unclear. Nevertheless the strategy proposes that

"[a]ction could include targeted change to the e-Commerce framework and the framework set out by Article 20 of the Services Directive". Arguably a relaxing of geo-blocking within the EU would harmonize the market, especially with the emergence of prominent internet based media services; however, it still leaves the abuse of cheaper pricing (or conversely, the pricing out of poorer regions) in the market in the light of this potential change.

The first pillar also includes a proposal to allow for a more fluid, easier access to content within the EU in terms of its legislative base. The strategy notes that

"[b]arriers to cross-border access to copyright-protected content services and their portability are still common, particularly for audiovisual programmes. As regards portability, when consumers cross an internal EU border they are often prevented, on grounds of copyright, from using the content services (e.g. video services) which they have acquired in their home country". This can be argued to relate to the point above quite heavily, with copyright ensuring the effective enforcement of geo-blocking, or any curtailment thereof. Some issues to persist, such as the inaccessibility to content for which you have rightfully paid for outside of some jurisdictions, as has been noted in the strategy as well, but these issues, at least in this writer's anecdotal experience, don't seem to be too prevalent.

The strategy also discusses a lack of clarity within copyright in the EU, but does not state as to what is unclear and how it is proposed to be remedied. Ending the first pillar, it is suggested that

"...the Commission will propose solutions which maximise the offers available to users and open up new opportunities for content creators, while preserving the financing of EU media and innovative content". While this is all well and good, no actual legislative measures are proposed, and the aim of the strategy in relation to copyright seems foggy at best.

The first pillar clearly envisions a freer, more affordable digital market within the EU, but omits the actual regulatory structures, or changes thereto, leaving the strategy with more questions than have been answered.

Pillar II - Creating the Right Conditions for Digital Networks and Services to Flourish

The second pillar builds on the first, with the proposal of a more robust, free and functional network, with basic rights and the assurance of content enforcement, especially in relation to third party operators such as ISPs. After discussions on the introduction of wider rules for telecoms, and the potential expansion of the

Audiovisual Media Services Directive, the strategy moved onto discussions on improving the online environment.

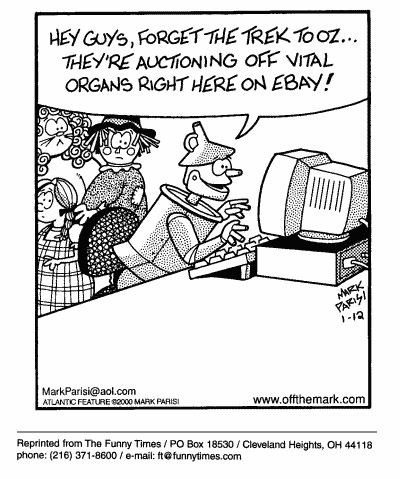

|

| Some pillars hold more than others |

The strategy brings up the restriction of certain players in the online world, such as search engines (

Google, anyone?) and media services. Issues raised

"...include a lack of transparency as to how they use the information they acquire, their strong bargaining power compared to that of their clients, which may be reflected in their terms and conditions (particularly for SMEs), promotion of their own services to the disadvantage of competitors, and non-transparent pricing policies, or restrictions on pricing and sale conditions". In this regard one has to agree to a certain extent, as e-commerce and other online giants become even bigger, their monopolies become harder to detect, and has the ability to curtail competition. How and when these issues would be tackled was also left out of the strategy, allowing for nothing but mere speculation at this point.

Illegal content online has been, and will be, a contentious issue, and the strategy does not leave it out either. Discrepancies with online enforcement of the removal of infringing content, and the blocking of such sources, can be said to be a thorn on the EU's side, and as the strategy points out:

"[d]ifferences in national practices can impede enforcement (with a detrimental effect on the fight against online crime) and undermine confidence in the online world". For the first time the strategy does bring up concrete steps as to how to deal with the issue of infringing content online:

"In tandem with its assessment of online platforms, the Commission will analyse the need for new measures to tackle illegal content on the Internet, with due regard to their impact on the fundamental right to freedom of expression and information, such as rigorous procedures for removing illegal content while avoiding the take down of legal content, and whether to require intermediaries to exercise greater responsibility and due diligence in the way they manage their networks and systems - a duty of care". Again, although more clear in its intent, the measures proposed have been left quite convoluted, a 'duty of care' on ISPs (and other third parties, possibly) could become too onerous, especially with more and more infringing content popping up online daily. With a sufficient allowance for flexibility, yet robustness, a duty of care system, or something akin or related to, could allow for the better enforcement of intellectual property rights online, while still allowing for its dissemination, sharing and other uses that fall within the scope of any exceptions.

All in all the EU digital environment, at least

prima facie, would seem to have a bright future, but with a substantially sized caveat included. How intermediaries are treated in this new environment, with the expansion of rules on telecoms, could hinder the sharing and dissemination of content online, as has been seen with the

DMCA in the US, if left too broad. This means any legislative initiatives would have to take both interests, being end-users' and commercial interests, into account when moving forward with any new legislative frameworks.

Pillar III - Maximising the Growth Potential of our European Digital Economy

Finally, the third pillar aims to add the last piece to the puzzle built on the two other pillars by creating more standardized platforms and technologies within the EU, and the improvement of digital skills and e-governance in the internal market. While largely irrelevant to a IP-heavy discussion, they still seem to add to the strategy in allowing for a more developed online network where these rules can operate. This article won't delve into the third pillar much, as it mostly does not relate directly to IP, but it is worth a read for anyone interested in the more practical aspects of the digital market.

Conclusion

While this writer can air nothing but his disappointment in the content of the strategy above, he is left to wonder why the proposal lacks so much in substance when the earlier leak seemed to offer more concrete terms of operation and improvement. With so much uncertainty in its future application, the Digital Single Market leaves with a whimper, and it remains to be seen how its final incarnation will impact on the EU and its legal (and practical) framework. The removal of barriers to enjoyment, and the possible harmonization of pricing and/or licensing in the EU seems, at least from a very superficial interpretation, a very welcomed change, how and when this would be done is still a big question as well.

As said, the strategy left much to be desired, but this writer remains hopeful.