The case of Nintendo Co. Ltd v BigBen Interactive GmbH dealt with the manufacture sale of remote controls and other accessories for the Nintendo Wii gaming console by BigBen, selling them online to consumers in France, Belgium and Luxembourg, and to its German subsidiary. The German entity sold the goods, manufactured by BigBen in France, to consumers in Austria and Germany. The German entity in itself does not hold any stock, but orders them when needed from the French entity. Both companies used images of the Wii and its official accessories (protected by registered designs, e.g. here and here) in the sale of these goods. Nintendo took both entities to court in Germany for design infringement.

The CJEU faced three questions in the matter, specifically dealing with whether the court of a Member State has jurisdiction over the matter where the infringement happened elsewhere; is this use allowed as citation under EU law; and how the place of infringement would be determined.

The first question, as summarized by the court, asked in essence whether the Community Designs Regulation (along with Article 6(1) of the Jurisdiction Regulation) gives jurisdiction to a court to impose an injunction against a party who is supplied by another party in another Member State for infringement of a registered design.

According to the CJEU, "…the territorial jurisdiction of a Community design court seised of an action for infringement within the meaning of Article 81(a)… extends throughout the European Union also in respect of the defendant who is not domiciled in the Member State of the forum". This means that there would be no jurisdictional issue with regards to pursuing a company in a different Member State through a national court within the EU.

The court then moved onto the second issue of use of the design as a citation. The question posed to the court, in short, asked whether Article 20 of the Community Designs Regulation meant that the use of a registered design by a third party, without authorisation, to demonstrate goods being sold online would be use as a citation and therefore allowed.

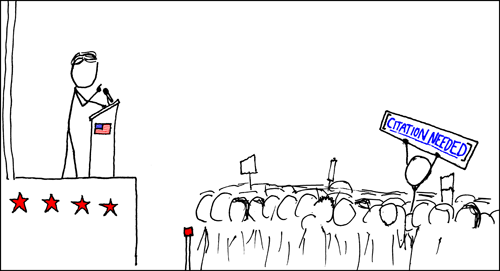

|

| Burt definitely needed a citation (Source: xkcd) |

The first condition look at whether the reproduction of the design falls within 'honest practices in industrial or commercial matters', i.e. should the design be reproduced in such a way as to create an impression of a commercial connection between the two entities, it would not be made for the purpose of citation. The second condition concerns the reproduction of the design that negatively affects the economic interest or their normal exploitation by the rightsholder. The third condition is simply attribution, so that a reasonable and observant consumer will know the design's commercial origin.

The court concluded that in the matter at hand the reproduction would be for the purpose of citation if it fulfils all of the above conditions.

Finally, the court addressed the last question of where the infringement would be committed between the two group companies, as the group companies reside and have committed infringements in several EU Member States. The CJEU, having considered the legislative framework, considered that "…the ‘country in which the act of infringement was committed’ within the meaning of Article 8(2) of that regulation must be interpreted as meaning that it refers to the country where the event giving rise to the damage occurred, namely the country on whose territory the act of infringement was committed". This hones down the legislation as applying to where the act was committed, rather than the damage occurring (i.e. infringement in Germany damaging a country in France).

As acknowledged by the court, IP does leave this interpretation as difficult, since the act could happen in a variety of locations in one time. In the light of this, the CJEU set out that "… where the same defendant is accused of various acts of infringement falling under the concept of ‘use’ within the meaning of Article 19(1) of [the Community Designs Regulation] in various Member States, the correct approach for identifying the event giving rise to the damage is not to refer to each alleged act of infringement, but to make an overall assessment of that defendant’s conduct in order to determine the place where the initial act of infringement at the origin of that conduct was committed or threatened". In the situation in the current matter, the place where the goods were put on sale online would be where the infringement took place.

The CJEU's decision is a very interesting one, and while they made no assessment on the particular infringements in the case, it still gives national courts the tools to do so themselves in a more flexible manner rather than just designating each infringement in its respective country. This will make the assessment of infringement, and similarly of citation, much clearer for the future.