Hot off the heels of the recent decision in Oracle v Google, copyright protection in computer programming is facing its latest hurdle, which is this time in the European courts. A big aspect of computer software management is the fixing of ever-present errors, be it due to the implementation of the software or the software in isolation. When you encounter such bugs you might have to decompile the program, which, to put simply, means to convert an executable computer program into source code, allowing you to fix errors and then to recompile the program to enable its execution. While decompiling can be used for more nefarious purposes (such as to enable the 'cracking' of protected software), it can allow for the fixing of legitimate issues in licensed copies of software. But, because of this potential nefarious way of using decompilation, would doing so breach copyright? Luckily the CJEU is on the case, but before the main court has looked at the issue Advovate General Szpunar gave his two cents a little while ago.

The case of Top System SA v Belgian State concerned a number of applications developed by Top Systems for the Belgian Selection Office of the Federal Authorities (also called SELOR), including SELOR Web Access and eRecruiting, which is in charge of the selection and orientation of future personnel for the authorities' various public services. Many of the applications developed by Top Systems contained tailor-made components according to SELOR's specifications. In February 2008 Top Systems and SELOR agreed on a set of agreements, one of which concerned the installation and configuration of a new development environment as well as the integration of the sources of SELOR’s applications into, and their migration to, that new environment. As with many projects, there were issues which affected the various applications. Following these problems Top Systems took SELOR (and the Belgian state) to court for copyright infringement due to the decompilation of Top Systems' software. After the usual progression of the matter through the Belgian courts the matter ultimately ended up with the CJEU, and also the desk of the AG. The referring court asked the CJEU two questions.

The first question asked "...whether Article 5(1) of Directive 91/250 permits a lawful acquirer of a computer program to decompile that program where such decompilation is necessary in order to correct errors affecting its functioning".

The AG first noted that, while computer programs have copyright protection over the reproduction of the program, it is limited due to the nature of how computer programs work (i.e. they need to be reproduced on a computers memory to operate). Strict enforcement would impede consumers' use of computer programs and therefore isn't desirable. The same applies to the protection against alteration. The Directive above does take account of this and sets out that reproduction and alteration of computer programs "...do not require authorisation by the rightholder where they are necessary for the use of the program by the lawful acquirer, including for error correction". However, Article 5 does leave the possibility open to restrict these acts through contractual provisions.

Even with that being a possibility, the ability to contractually restrict the reproduction or alteration is there, this cannot extend to all such activities, as the acts of loading and running of a computer program necessary for that use may not be prohibited by contract.

The AG then moved onto the matter of decompilation for the purposes of correcting errors. He agreed with the submissions made by the interested parties in that decompilation is covered by the author's exclusive rights under the Directive, even though there is no express 'decompilation' provision there.

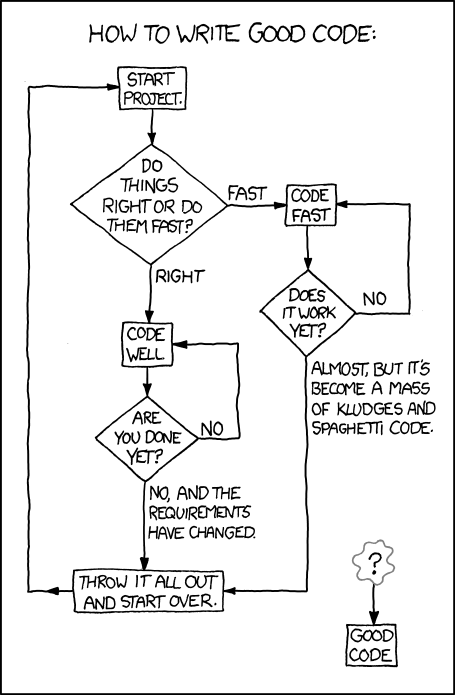

|

| Gary wanted to fix the software, but his hands were tied... |

Although argued by TopSystems, decompilation cannot be excluded from those rights under Article 6 according to the AG (which allows for reproduction and translation of a computer program if it is indispensable for the operation of the program with other programs). The relevant provision therefore remains at Article 5 and 6 will have no bearing on the exclusion of decompilation. Article 6 does not stand as the only instances where it is possible to decompile a computer program.

The AG therefore proposed that the first question be answered as "... Article 5(1)... is to be interpreted as permitting a lawful acquirer of a computer program to decompile that program where that is necessary in order to correct errors affecting its functioning".

He then moved onto the second question which asked "...in the event that Article 5(1)... were to be interpreted as permitting a lawful acquirer of a computer program to decompile that program where that is necessary in order to correct errors, that decompilation must satisfy the requirements laid down in Article 6 of that directive or, indeed, other requirements".

Article 6 sets out, as discussed above, the decompilation of a computer program where that is necessary in order to ensure the compatibility of another independently created program with the program. The AG discussed the specific requirements under Article 6, namely that: (i) they only apply to those who have lawfully acquired the program; (ii) the decompilation must be necessary in order for that program to be used in accordance with its intended purpose and for error correction; and (iii) the intervention of the user of the computer program must be necessary from the perspective of the objective pursued.

In relation to the second condition, the AG noted that an 'error' should be defined as "...a malfunction which prevents the program from being used in accordance with its intended purpose". One has to note that this does not include the amendment and/or improvement of a program, but simply the enabling of the use of the program for its intended purpose.

On the third condition, the AG specified that, while the decompilation of a program can be necessary, it always isn't. He determined that "...the lawful acquirer of a computer program is therefore entitled, under [Article 5(1)], to decompile the program to the extent necessary not only to correct an error stricto sensu, but also to locate that error and the part of the program that has to be amended". So, a lawful user can decompile a program to both fix and locate any errors, which gives them quite a wide berth in doing so. Nonetheless, the AG noted that the decompiled program cannot be used for other purposes.

The AG therefore proposed the answer to the second question as "...Article 5(1)… is to be interpreted as meaning that the decompilation of a computer program... by a lawful acquirer, in order to correct errors in that program, is not subject to the requirements of Article 6 of that directive. However, such decompilation may be carried out only to the extent necessary for that correction and within the limits of the acquirer’s contractual obligations".

The CJEU's decision will be an interesting one and will undoubtedly impact the ability of programmers and companies to decompile computer programs to correct any errors they might find during the use of said programs. It would make sense to allow for their decompilation for this restricted purpose, since without that right major errors could render programs useless until the point when the provider can, and decides to fix those errors. It remains to be seen whether the CJEU will agree with the AG, but it would seem sensible for them to follow his responses.