The discussion of news, cases, legislation and anything to do with Intellectual Property law (and associated topics), made accessible to everyone.

12 April, 2022

Data in the Clouds - CJEU Accepts the Use of the Private Copying Exception in Relation to Cloud Storage

10 August, 2021

Copying Not Allowed - Search Engines Copying Databases Infringes Database Rights If It Causes Financial Detriment, says CJEU

Following an earlier opinion from the Advocate General, the CJEU set out its findings on the infringement of database rights by search engines in the indexing of other websites' content. Discussed earlier in this blog, the decision is an important one to set the potential boundaries of database rights and indexing, especially when indexing is so ubiquitous in how the Internet as we know it functions. The decision will leave some rightsholders wanting more, as now the position swings firmly in the direction of the indexing websites.

The decision in CV-Online Latvia SIA v Melons SIA concerned the website CV-Online, which included a database of job advertisements published by various employers. The website also included various metatags, or 'microdata', which, while not visible to the users of the website, contained key information to allow internet search engines to better identify the content of each page in order to index it correctly. These metatags included keywords like ‘job title’, ‘name of the undertaking’, ‘place of employment’, and ‘date of publication of the notice’.

Melons operate a separate website containing a search engine that specializes in job ads. The search engine allows users to search a number of websites containing job ads in one go according to specific criteria that they set. The Melons' website then produces results based on that search, where users can click on links that take them to that particular job website where the ad is located (including CV-Online). Unhappy about this indexing of their content, CV-Online took Melons to court for a breach of their 'sui generis' right under Article 7 of Directive 96/9. The case progressed through the Latvian courts, ultimately ending up with the CJEU this Summer.

The CJEU was asked two questions, which the court decided together.

The question posed to the court asked: "whether... the display, by a specialised search engine, of a hyperlink redirecting the user of that search engine to a website, provided by a third party, where the contents of a database concerning job advertisements can be consulted, falls within the definition of ‘re-utilisation’ in Article 7(2)... and... whether the information from the meta tags of that website displayed by that search engine is to be interpreted as falling within the definition of ‘extraction’ in Article 7(2)(a) of that directive".

The court first discussed 'sui generis' rights in general, which allow rightsholders to ensure the protection of a substantial investment in the obtaining, verification or presentation of the contents of a database. What is required for a database to be protectable is "...qualitatively and/or quantitatively a substantial investment in the obtaining, verification or presentation of the contents of that database". Without that investment, the courts will not protect any databases under sui generis rights. The court assumed that this would be the case in terms of CV-Online, however, this matter would ultimately be decided by the local courts following the CJEU's decision.

For there to be an infringement of sui generis rights there has to be an ‘extraction’ and/or ‘re-utilisation’ within the meaning of Directive, which, as summarised by the court, includes "...any act of appropriating and making available to the public, without the consent of the maker of the database, the results of his or her investment, thus depriving him or her of revenue which should have enabled him or her to redeem the cost of that investment".

The court discussed the applicability of the above to the operation of Melons' website and determined that such a search engine would indeed fall within the meaning of extraction and re-utilisation of those databases that the website copies its information from (including in indexing that content). However, this extraction/re-utilisation is only prohibited if it has the effect of depriving that person of income intended to enable him or her to redeem the cost of that investment. This is important since without this negative financial impact the copying will be allowed under EU law.

The court also highlighted that a balance needs to be struck between the legitimate interest of the makers of databases in being able to redeem their substantial investment and that of users and competitors of those makers in having access to the information contained in those databases and the possibility of creating innovative products based on that information. Content aggregators, such as Melons, are argued to add value to the information sector through their acts and allow for information to be better structured online, thus contributing to the smooth functioning of competition and to the transparency of offers and prices.

The referring court would therefore have to look at two issues: (i) whether the obtaining, verification or presentation of the contents of the database concerned attests to a substantial investment; and (ii) whether the extraction or re-utilisation in question constitutes a risk to the possibility of redeeming that investment.

The court finally summarised its position on the questions as "...Article 7(1) and (2)... must be interpreted as meaning that an internet search engine specialising in searching the contents of databases, which copies and indexes the whole or a substantial part of a database freely accessible on the internet and then allows its users to search that database on its own website according to criteria relevant to its content, is ‘extracting’ and ‘re-utilising’ the content of that database within the meaning of that provision, which may be prohibited by the maker of such a database where those acts adversely affect its investment in the obtaining, verification or presentation of that content, namely that they constitute a risk to the possibility of redeeming that investment through the normal operation of the database in question, which it is for the referring court to verify".

The decision will, as said above, come as a big blow to database owners, as the added requirement of financial detriment will be a big hurdle for many to overcome in order to protect their databases from potential copying. The CJEU also notes the utility of indexing and the 'copying' of such databases by content aggregators as useful means of organizing the Internet, which leads to the question of where the limits actually are. It will remain to be seen how the decision will impact databases going forward, but one might imagine the more commercial value in a database the less likely the courts will allow copying of that database.

13 April, 2021

Not as the Oracle Foretold - US Supreme Court Decides on Copyright Infringement in relation to APIs

APIs, or Application Programming Interfaces, are absolutely everywhere these days. APIs allow for two pieces of software to 'speak' with each other, sharing information across to allow for interactivity and interconnectivity between different software applications. While many providers share their APIs freely for implementation, there is still certain rights that attach to those APIs in the form of copyright over the code itself. Just like text in a book, code can be protected by copyright and, in many instances, is absolutely worth protection if a particular coding language becomes very popular. This has been the central focus of an epic legal battle between Oracle and Google in the US, which has spanned for nearly 10 years (discussed previously on this very blog), and the highly anticipated US Supreme Court decision has finally been handed down in early April 2021.

The case of Google LLC v Oracle America Inc. concerned the Java SE program, which uses Oracle's Java programming language. Parts of the Java SE program's code (roughly 11,500 lines of code) was used in the development of Google's Android operating system, which formed a part of the Java SE API. Java SE is commonly used to develop programs primarily to be used on desktop and laptop computers, which also extends into the realm of smartphones. Oracle subsequently sued Google for copyright infringement over this copied code, and the matter finally ended with the Supreme Court after a long 10-year journey through the US courts.

The Supreme Court were tasked at looking at two questions: (i) whether Java SE’s owner could copyright the portion that Google copied; and (ii) whether Google’s copying nonetheless constituted a “fair use” of that material.

Justice Breyer, handing down the majority's judgment, first started off discussing the basic requirements for copyright protection. This means that the work has to be one of authorship, original and fixed in a tangible medium. Copyright encompasses many types of works, such as literary, musical and architectural works, but in a more unconventional manner it includes 'computer programs', which are "...a set of statements or instructions to be used directly or indirectly in a computer in order to bring about a certain result". In terms of limitations, copyright does not extend to "...any idea procedure, process, system, method of operation, concept, principle, or discovery". In addition to copyright protection in general, one has to consider the remit of 'fair use', which allows for the use of copyright protected works for various purposes, e.g. criticism, satire and news reporting.

The first question, as set out above, concerned whether the provision extending copyright protection to 'computer programs' includes APIs and/or whether they are excluded as 'processes', 'systems' or 'methods of operation' from copyright protection. However, the Supreme Court skipped the copyright aspect of the matter and immediately dove into whether Google's use of the API was fair use.

Justice Breyer noted that computer programs differ from other 'literary works' in that such programs almost always serve functional purposes, which makes the application of copyright to them more difficult. He also mentioned that, in discussions to extend copyright to computer programs, it should not "...grant anyone more economic power than is necessary to achieve the incentive to create". The key is to not allow copyright to stifle innovation in the realm of computer programs.

Justice Breyer also mentioned that fair use can be used to distinguish between expressive and functional features of computer code where those features are mixed, and allow for different programs to be more readily distinguished in the light of protection.

Turning to actually considering whether Google's copying fell into fair use, the Supreme Court had to look at the well-established factors of fair use: (i) the nature of the copyrighted work; (ii) the purpose and character of the use; (iii) the amount and substantiality of the portion used; and (iv) market effects.

In relation to the first factor, the Supreme Court discussed the use of APIs in general as a way for computer programs to speak to each other. APIs also comprise three different 'functional' aspects, which are various parts of code that handle different aspects of the APIs functionality. Justice Breyer highlighted that the parts are inherently functional and bound together by uncopyrightable ideas (i.e. task division and organization) and new creative expression in the form of Android's implementing code. In their view the nature of APIs diminishes the need for copyright protection over them.

In terms of the second factor, the focus is on the transformative nature of a copyright protected works use. Google sought to make new products using the API and to expand the usefulness of the Android OS - argued to be transformative and innovative around the copying of the API. The Supreme Court also noted that one has to consider both the commerciality and good faith in relation to the copying. Justice Breyer determined that, while Google's use of the API was a commercial endeavor, it doesn't mean that the use cannot be transformative. Good faith was not a consideration in the case, but Justice Breyer did highlight that the other factors on the copying of the API weight towards a finding of fair use.

The Court then moved onto looking at the amount of the work copied. As discussed above, Google copied approximately 11,500 lines of code, which was a mere fraction of the totality of 2.8 million lines in Java SE. While the amount is important, it's the substance of what was copied that is the most important part when thinking about substantiality. Why the lines were copied was to enable Java experienced programmers to work with Android; without which this would have been very difficult. This objective for the copying was to enable the expansion of Android, not to replace Java SE, and the Court did see that this favored a finding of fair use.

Finally, the Court turned to the market effects of the copying, i.e. did it impact the market value of the protected work. Thinking of the use of the code, it was in a market sector where Sun Microsystems (Oracle's predecessor) was not well-positioned, and the primary market for Java SE was PCs and laptops. Android used in smartphones was in no way a substitute for traditional computers where Java SE was typically used. However, the code's implementation did benefit Android through attracting developers to improve the OS. The Court saw that the copying didn't impact Sun Microsystem's position in the marketplace, and issues with an impact on creativity within the development of programs like Android, weighed for a finding of fair use.

Rounding things off, Justice Breyer discussed the application of copyright in the world of computers and the difficulties the old concept has in adapting to this new environment. In his view, copyright very much persists in computer programs (and their underlying code), but emphasized the fair use doctrine's place in the same.

The Supreme Court ultimately concluded that Google's copying was fair use as a matter of law and therefore there was no infringement of Oracle's code.

The case is a massive milestone in the application of copyright in computer programs and code, and as the court observed, Google only took "...what was needed to allow users to put their accrued talents to work in a new and transformative program". This is curious and can open the door for others to copy code as and when needed, without licensing, if it is used to allow for innovation through the implementation of well-established technologies. Justice Thomas did indeed write a very strong dissent to the majority's verdict, which highlights the blurring of copyright in relation to code. It remains to be seen how this precedent is applied by the courts in future cases, but it could very well lead to the limits of fair use in relation to code being tested sooner than you think.

22 March, 2017

A Gentleman's Code - The Copying of Software Code and Copyright

The case of IPC Global Pty Ltd v Pavetest Pty Ltd (No 3) dealt with equipment used to test asphalt and construction materials, built by IPC, which included custom programming to enable the user to test said materials and view results. This piece of software was installed on the users' computer. Two individuals, Con Sinadinos and Alan Feeley, worked at IPC (with the latter working as a consultant as a part of Alueta). The pair then resigned from IPC in 2012, establishing a competitor company, Pavetest, which launched competing testing products. Mr Feeley had in his possessions copies of IPC's programs on his computer that he took with him when leaving IPC. He then provided them for a programmer who made copies of the programs, leaving some parts of the Pavetest identical to that of IPC's programs. IPC then took Pavetest (and the individuals) for, among other claims, copyright infringement and breach of confidence.

Although Justice Moshinsky had a wide array of issues to decide, focus for the purposes of this article will remain on the question: "...did Pavetest infringe copyright in the UTS software by the creation of version 1 of the TestLab software? In particular, did version 1 of the TestLab software reproduce a substantial part of the UTS software?"

After discussing, at length, the companies and the development of the two competing pieces of software, the court focussed on the matter of copyright infringement.

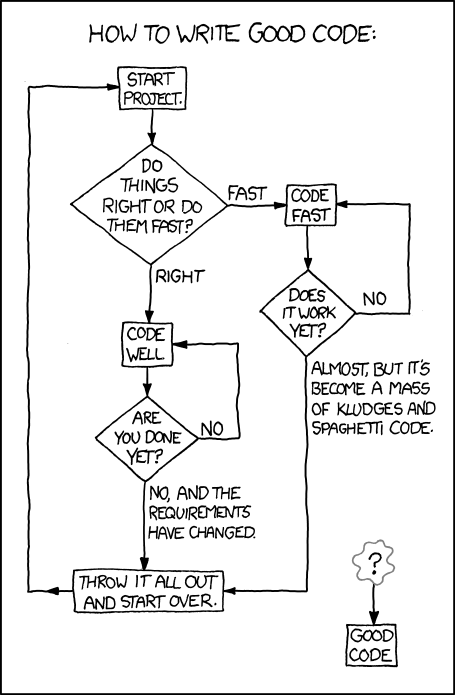

|

| Original code? Nah... (Source: xkcd) |

The courts have developed a test to determine whether a computer program has been infringed, there is ‘the need for some process of qualitative abstraction of the material features of the computer program in question’, and the copying of those features in the potentially infringing program (i.e. of a program calculates figures based on data, the program features of the calculation would be more important than the aesthetic function of the same under this context).

While the respondent conceded that the code is a copyright protected work, that substantial parts of the code were copied (but not to the degree of being a substantial part under section 14), and that this was done on behalf of Pavetest with the authorization of the individuals above, the court still had to consider whether the copying was indeed substantial under the law.

Due to the coder working for Pavetest to be able to rewrite the code so as the new version didn't infringe IPC's copyright, there clearly was a wide margin of expression in how the code could be implemented, while still having the same functionality. The writing of the code therefore included a degree of choice and judgment, making the expression of that functionality original under copyright. While some parts of the code would not be essential, Justice Moshinsky still upheld that they were original works equally to those parts that were essential. Finally, the amount of code, albeit a small amount (roughly 10,000 lines of code from about 250,000 lines), the copying was substantial, according to the judge, due to its necessity to achieve the desired functionality, rather than just simply through a quantitive measure. Pavetest had subsequently infringed the rights in the code.

The case is a very interesting one, and highlights a need for anyone copying others' code (which seems to be an industry standard, albeit only in parts of programming) to be cautious, and to rewrite anything that could be deemed to be a substantial copying. Software creation is incredibly complex and difficult, and one can appreciate the adoption of shortcuts, but the courts will clearly combat any abuses of others copyright works, even if it's just 'meaningless' code.

Source: IP Whiteboard

15 November, 2013

Irish Copyright Review: Modernizing Copyright

The report is very extensive, touching upon most contentious areas of copyright and attempting to suggest changes to the currently in-force Irish Copyright and Related Rights Act 2000. While all of the topics discussed merit further evaluation and offer much to the current discourse of copyright not just in Ireland, but also globally, discussion will be left to only parts of the report by this writer.

Fair Dealing

One of the biggest questions in copyright globally is the line where fair dealing (or fair use) should be drawn, and Ireland is no exception to this. Under the current Act Ireland has a very limited fair dealing scheme which allows for the use of copyrighted materials in research and private study and in criticism or review. The report does recognize the incredibly limited nature of the current regime and attempts to remedy its shortcomings under the recommendation "...that the existing exceptions be regarded as examples of fair use, that they must be exhausted before analysis reaches the question of fair use, and that the question of whether a use is fair on any given set of facts turns on the application of up to eight separate factors". These factors would include a very wide scope of consideration, varying from the purpose and nature of the copying to the possibility of obtaining the work legally; a lot of which resemble considerations already used in a number of other common law countries.

The report actively tried to distinguish its approach to fair use from the often used US fair use doctrine, which has been adopted in a number of nations even outside of the common law, but the suggested regime does not differ largely from its US counterpart as presented. It does go further in its considerations and presents Irish courts with more specific factors to use, but one can clearly see the connection with the American provisions. All in all the suggested changes are incredibly welcome, and showcase the importance of fair dealing in copyright; something which this author and others have advocated on a number of occasions. In addition very similar considerations were put forth in the Australian submissions for reform; however their final form is still pending the release of the final report by the Australian Law Review Commission.

Intermediaries

The report also deals with the role of intermediaries in potential infringement situations, considering more clear immunity provisions to the ones already provided under Irish law. The report proposes changes which would bring these immunities better in line with the European Union Copyright Directive.

After the tightening up of already existing provisions the report also suggests further protection of potential secondary infringers, especially as "...in the current regime, intermediaries bear a significant burden in implementing monitoring or “notice-and-action” procedures, and there are arguments as to whether this burden is a legitimate cost of doing business as an intermediary or an unjust cost of protecting rightsowners’ rights". This would be a EU matter to further legislate on and provide clarity, as the provisions relating to this are largely of EU origin.

In addition the report suggest a potentially more proactive approach by the Irish legislature to introduce immunity provisions specifically relating to search engines, immunity as a result of the sophistication of internet browsers (in other words, the displaying and caching of copyrighted content, causing the browser to being the primary infringer), and immunity provisions relating to cloud computing. As the report states: "...Irish law should await whatever legislative proposals emerge from the EU consultation. If nothing comes of it, then it may be appropriate at that stage to return to the question of Irish legislative immunities". Immunities over linking to content were also discussed, raising the recent UK Supreme Court decision of Public Relations Consultants Association Ltd v The Newspaper Licensing Agency Ltd as an example of taking these immunities in an express direction.

Users

The extent to which you can use your legally acquired content has been a contested issue in copyright for decades. The report poignantly raises the heart of the issue: "...the centrality of rightsowners in copyright law, but the law recognises other interests as well, and seeks to balance the interests of rightsowners in protecting their monopoly against other legitimate interests in diversity and expression". The balance between expression and creation by the end-user against the rightsowners' interests is paramount, but clearly there have been issues on the balance being swayed towards the rightsowners in recent years.

In addition to the aforementioned fair dealing considerations the report raises the potential to add new exceptions for private use. Private copying is largely supported by both sides, and in itself supports "...users’ reasonable assumptions and basic expectations" relating to the use of their legally acquired content. This has been suggested in the above EU Directive, and the report endorses its introduction into Irish law. Certain reproduction rights relating to different formats and back-ups were endorsed, again reflecting the reasonable assumptions made by users over their material.

An exception for parody, caricature and satire was also suggested, reflecting a much larger introduction of this exception in the common law; one which has been introduced in Australia a while ago. Following the recent changes in Canada the report also suggests the creation of a non-commercial user generated content exception. Although not expressly mentioned in the above EU Directive, the report still recognizes its inclusion in spirit and supports its express introduction into Irish law.

Conclusion

Even though the report is far more extensive than what is discussed above, it showcases a wave of change in copyright globally. This change has been late in its introduction, with still years till the potential changes would even be implemented, but shows a willingness to adapt and mold the law to modern users and spheres. This writer endorses this and highly awaits the final report here in Australia late this month in further assessing where things will go. Right now Ireland is paving the way in the wake of the change in the common law.

29 August, 2013

Free Textbooks for All?

| A familiar sight to most University students |

What Mr. Lear is doing is providing free PDF copies of textbooks for certain classes, while encouraging others to share their books in an equal fashion. He has also passed on flyers which contain scannable links to copies of textbooks which students can download directly onto their phones, tablets and computers. This, in Mr. Lear's mind, is purely an action against both the publishing industry and the book stores which provide legitimate copies of books both on and off-campus.

So what could Mr. Lear be liable for? Under US copyright legislation there is no particular provision which imposes secondary liability, although there are provisions which protect from it. The courts in Intellectual Reserve v Utah Lighthouse Ministry saw that the situation is not completely black and white even though there are no provisions for secondary liability: "Although the copyright statute does not expressly impose liability for contributory infringement, the absence of such express language in the copyright statute does not preclude the imposition of liability for copyright infringements on certain parties who have not themselves engaged in the infringing activity".

Indeed one could argue that Mr. Lear could be liable for contributory infringement through inducement, due to the fact that he is fully aware that the people he distributes the information and links to can infringe copyright, and arguably do so when presented with the option. He actively participated in his cohorts' infringement, knowing full well that they are using his methods to create infringing copies of textbooks (cases which deal with the subject matter more extensively are Sony Corporation v Universal Studios and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios v Grokster). In his own words he intends to utilize mass infringement as a means to overthrow the current copyright system for another, clearly presenting a motive to compel others to infringe copyright.

The world of academia is harsh and unforgiving, both financially and intellectually. Although one can be sympathetic to the financial hardship that modern students face, having personally experienced it for the last few years myself, Mr. Lear's approach and mentality are not ones which harbor a healthy and open forum of discussion and change. Should students be able to contravene long-standing copyright laws and practices purely to save money? The answer from a legal stand-point is a simple no, but arguably there is room for improvement on part of both the publishers and institutions of higher education. Whether Mr. Lear will be taken to court remains to be seen, but should his movement start spreading into the wider United States publishers would have incentive to do so to nip the issue at the bud.

Source: TorrentFreak

04 August, 2013

Retrospective - The Nature of Copyright

The case dealt with Mr. Kenrick and Mr. Jefferson who owned a printing and publishing company called the Free Press Company. During the 1800s, Mr. Jefferson had noticed that illiterate voters had a hard time understanding how to vote, effectively consisting of drawing a cross in a certain part of a piece of paper indicating who you would vote for, without the aid of a picture or pictures showing them exactly what to do. In attempting to resolve this he sought the help of Mr. Bott to draw a hand drawing a cross in an enclosed box, as per his own initial sketch. Mr. Bott did exactly that, and the drawing was determined to being the creation of Mr. Jefferson and the property of his company under the Fine Art Copyright Act 1862. Subsequently the defendant, Mr. Lawrence, published a similar informational card where the hand was in a slightly difference position also finishing a cross in a blank box, and was sued by the plaintiffs for copyright infringement.

| An incredibly 'complex' form of expression |

Looking at the issue at hand, should the 'idea' of a hand drawing a cross be protected by copyright? The court in its judgment rejected this notion. In his opinion Justice Wills saw that if the work is copied exactly, there could be an infringement, but if the idea of a hand drawing a cross is used but expressed in a different manner, as what Mr. Lawrence had done, there would not be infringement. Offering Mr. Jefferson protection for the concept of a hand drawing something would impede others from drawing anything similar, as anyone attempting to draw a hand drawing something would inevitably end up with something similar to what Mr. Jefferson had produced. Justice Wills did admit however, that the more skill and labor has been put into a work, the more protection will be offered to it as a consequence. In summarizing the court's position, Justice Wills stated that:

"It seems to me, therefore, that although every drawing of whatever kind may be entitled to registration, the degree and kind of protection given must vary greatly with the character of the drawing, and that with such a drawing as we are dealing with the copyright must be confined to that which is special to the individual drawing over and above the idea - in other words, the copyright is of the extremely limited character which I have endeavored to describe. A square can only be drawn as a square, a cross can only be drawn as a cross, and for such purposes the plaintiffs' drawing was intended to fulfill there are scarcely more ways that one of drawing a pencil or the hand that holds it. If the particular arrangement of square, cross, hand, or pencil be relied upon it is nothing more than a claim of copyright for the subject, which in my opinion cannot possibly be supported."Copyright does not serve as to protect broad concepts like ideas, but a very specific expression of those ideas. The complexity of the work will play into its protection, as more abstract concepts are harder to recreate without any influence or copying of the original work, but simple concepts can be recreated without any prior knowledge of them due to their simple character. Once this is understood, copyright finally shows its true colors and intent, and more detailed considerations in any given case can be assessed.

03 July, 2013

Retrospective - Betamax and Copyright Infringement

| "What is this 'video cassette' you speak of..?" |

For Sony to be deemed to be liable under contributory infringement, the court had to decide whether Betamax recorders are capable of commercially significant non-infringing uses. This could be seen as whether the non-infringing uses would impact Universal Studios, or others, commercially through those uses. The court stated that it would be a matter of exploring all possible uses for the machines and determining whether those uses would be infringing or not, and what amount of uses would be commercially significant. The court did decide that Betamax recorders could be capable of commercially significant non-infringing uses, but for Sony to be liable there still remained the factor of whether those uses would be infringing ones.

| How teenagers view older generations and themselves |

The court drew its attention to the US fair use provision in deciding whether domestic time-shifting would be an infringing act. The court accepted the District Court's findings and saw that domestic time-shifting of content would fall under fair use. This was due to Sony's evidence as to the licensing of content for broadcasting on free TV, and content providers not objecting to its recording for viewing at a later time, and Universal could not show any actual damage caused due to time-shifting.

The decision swayed 5-4 in favor of Sony, but the dissenting opinion given by Justice Blackmun could've shaped copyright in a wholly different manner should it have been the majority opinion. The dissenting view was one which emphasized the exclusive rights given to copyright owners, noting that in their opinion expanding fair use would take away control for the copyright owners and deprive them of their incentive to create. Justice Blackmun also noted that fair use should apply mainly to 'productive' uses of works, such as for criticism and review, and prohibit their uses for 'unproductive' purposes such as time-shifting. Arguably Justice Blackmun's views come from a wrong approach, one which protects the copyright holder's rights but completely ignores the evolving needs and uses by ordinary consumers, thus creating an imbalance. Justice Blackmun also criticized the majority's approach in deciding contributory infringement through the capability of commercially significant non-infringing uses in stating that "[s]uch a definition essentially eviscerates the concept of contributory infringement. Only the most unimaginative manufacturer would be unable to demonstrate that a image-duplicating product is "capable" of substantial noninfringing uses. Surely Congress desired to prevent the sale of products that are used almost exclusively to infringe copyrights; the fact that noninfringing uses exist presumably would have little bearing on that desire".

All-in-all Sony v Universal Studios made an important mark on copyright and fair use, and has helped in formulating current principles in both. Should Sony have been found liable for contributory infringement, how we record or enjoy media today could be totally different. Manufacturers would have to either pay hefty licensing fees for any recording devices, the cost of which would have been undoubtedly transferred onto the end-consumer, or the manufacturers would have refrained from producing such devices completely. As someone who grew up using VHS recorders to watch content, I can't imagine a World without such a capability.

23 June, 2013

The United Kingdom Looking Ahead with new Copyright Exceptions

Exception for Private Copying

In their plans, the UK Government plans to introduce "...a narrow private copying exception which will allow an individual to copy content they own, and which they acquired lawfully, to another medium or device for their own personal use". What this clearly is is an equivalent for something Australia has already had for some years; format shifting. Provisions such as this will allow you to copy your lawfully bought content, such as music or movies, to a different format - often from a CD onto your MP3 player for example. There is a distinct difference to what the UK approach, at least for now, is when compared to the Australian one. In further expanding on how the copying will extend, the IPO says that "...it would not allow them to make copies of their CDs and give them to other people". If this were to be looked at from a literal perspective, should you make a copy of a CD for your kids to listen to on their iPods, or give a copy of a DVD for your cousin to watch on a Saturday night, you would be infringing copyright. The Australian provision allows for copies to be given to family or people living in your household, but on the condition that those copies are of a temporary nature and not given to keep. If the IPO would only permit the copying for personal use in excluding family they would go against the very principle why they're enacting these additions to begin with: "The exception aims to align the law with behaviour most people consider to be reasonable, to remove unnecessary regulation, and to help build confidence in and respect for copyright".

| Steve hasn't quite gotten the hang of "private copying" |

Arguably the exception should be shaped to be similar to that of Australia's approach. The Canadian provision only allows for the copying for the individual, much like the potential UK provision, so the direction where this could head is unclear. One could easily predict that the courts could potentially extend the provision to apply to family, but that would remain to be seen. A draft of the section can be found in the document discussing the exception.

Exception for Parody

An exception that the UK has needed for the past several years, yet again lagging behind its Australian cousins, is the exception to allow for the use of works for parody, caricature or pastiche. As the IPO explained, this would "...give people in the UK’s creative industries greater freedom to use others’ works". If introduced the provision would be included with other fair dealing provisions, so the use would have to be 'fair', preventing the use of works in the veil of parody to purely abuse it for personal gain. A draft of the possible provision can be read in the IPO's documentation as well.

Exception for Quotation

The final exception being introduced is one which would amend the current exception for criticism and review to one allowing for the quotation of material, not merely restricting it to those uses. Broadening the existing fair dealing exception seems like a perfectly sensible option, and in the words of the IPO: "ensure[s] that copyright does not unduly restrict the use of quotations for reasonable purposes that cause minimal harm to copyright owners, such as academic citation or hyperlinking". Should the provision be enacted it would be the first of its kind, as both in Australia and Canada similar provisions relating to criticism and review, on the face of the provisions, would be much more restrictive.

Source: IP-Watch

13 June, 2013

Retrospective - Linking to Trouble

| An imagining of a potential MP3s4Free user |

|

| Don't click! |