The case of Joseph Matal v Simon Shiao Tam dealt with a rock band, The Slants, who sought to register their name as a trademark in the US. The term "slants" is a derogatory term for persons of Asian descent, and the band sought to, through the use of the negative term as their moniker of choice, to reclaim it and take away its negative meaning. After filing their application for the trademark, the USPTO denied the application on disparagement grounds under 15 USC section 1052(a). The band, under the name of its lead singer Mr Tam, challenged the ruling and took the matter all the way to the Supreme Court.

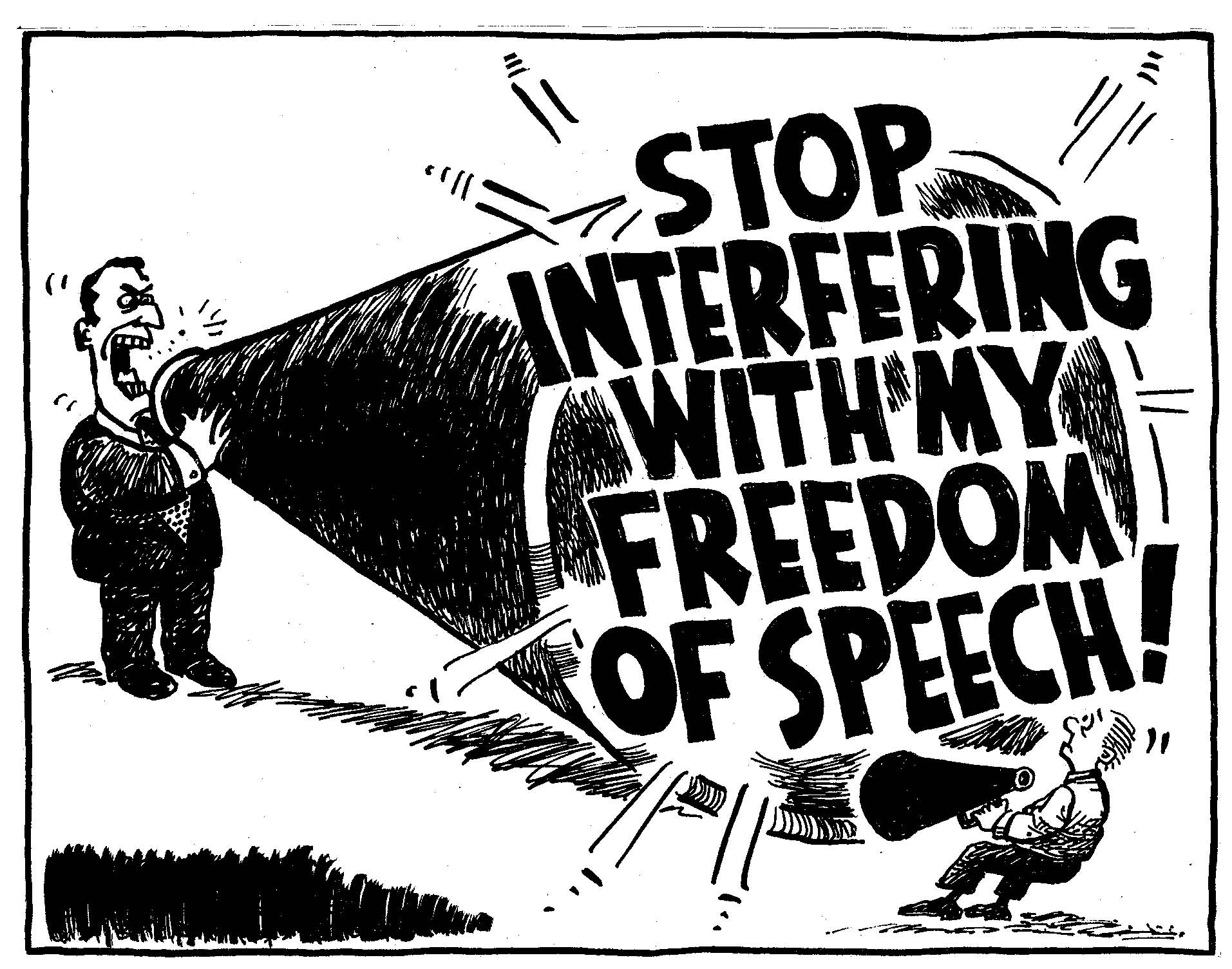

The crux of the case remained that would the clause preventing the registration of disparaging be unconstitutional, particularly in terms of the First Amendment right to free speech.

At first, after setting out the legislative history of trademarks, Justice Alito (delivering the majority's opinion) considered that, while there is a valid registration system for trademarks, one does not have to register a mark to enjoy its use. In the same vein, the marks can be protected on a federal level under the Lanham Act, particularly through common law rights in those marks. Even so, certain rights are conferred to the holders of the marks through registration, and it does therefore add value and further protections over those marks, making registration very important.

Justice Alito then moved onto the test of whether a trademark is disparaging. This is whether "…the likely meaning of the matter in question, taking into account not only dictionary definitions, but also the relationship of the matter to the other elements in the mark, the nature of the goods or services, and the manner in which the mark is used in the marketplace in connection with the goods or services… [and] whether that meaning may be disparaging to a substantial composite of the referenced group". Even if the applicant is of the 'disparaged' group of people does not negate any possible findings under the test. At first instance, both the USPTO and the Appeal Board determined that the mark sought was indeed disparaging.

Before discussing whether the clause is unconstitutional or not, the Court had to first look at whether the mark was, as determined at first instance, disparaging. Tam argued that, while the disparagement provision speaks of 'persons', it cannot apply to non-juristic entities such as ethnic groups, but only to natural and juristic persons (i.e. individuals and not undefined, albeit legally defined groups). The Court swiftly rejected this argument, as Tam's narrow construction does not match with that of the provision of USPTO's definitions, which set out much broader terms, speaking of not just 'persons', but also 'institutions' and 'beliefs'. Therefore, as the Court concluded, disparagement can apply to non-juristic entities just as well as juristic entities.

Justice Alito then moved onto the main focus of the case, i.e. the constitutionality of the disparagement clause itself.

|

| Washington's newest football team's logo (trademarked of course) |

The US government also argued that precedent set shows that government programs that subsidized speech expression specific viewpoints are constitutional. Justice Alito quickly rejected this argument, since "…[t]he federal registration of a trademark is nothing like the programs at issue in these cases". While registration does, arguably at least, confer certain non-monetary benefits to registrants, it does not provide a direct monetary subsidy, which the cases discussed did.

Finally, the government argued that the disparagement clause should be sustained applying only in cases that involved 'government-programs'. Justice Alito, again, rejected this argument, setting out that "…the public expression of ideas may not be prohibited merely because the ideas are themselves offensive to some of their hearers". The Court deemed that you cannot discriminate against a particular viewpoint, and the disparagement clause does do so, even if the subject matter is potentially offensive to a given group of people. The Court therefore concluded that "…the disparagement clause cannot be saved by analyzing it as a type of government program in which some content- and speaker-based restrictions are permitted".

The Court then finally moved onto the question of constitutionality. whether trademarks are commercial speech, and therefore can be restricted under limited scrutiny under Central Hudson. The case allows for a restriction of free speech that has to "…serve a substantial interest and it must be narrowly drawn". Justice Alito concluded that the clause fails the Central Hudson scrutiny on the outset. It was also argued that it serves two interests, including protecting underrepresented groups from abuse in commercial advertising. The Court dismissed this interest, as the First Amendment protects even hateful speech. The second one is protecting the orderly flow of commerce, where the trademarks, through their offense, prevent or reduce commerce through their use. Justice Alito dismissed this argument as well, as the disparagement provision is not 'narrowly drawn' to prevent the registration of only trademarks that support invidious discrimination, while applying to a very broad type of people, including the dead. In her final view "…If affixing the commercial label permits the suppression of any speech that may lead to political or social “volatility,” free speech would be endangered". The Supreme Court therefore deemed that the disparagement clause violates the First Amendment.

The case is a hugely influential one, which opens the door for a myriad of trademarks, particularly those that are offensive or have the potential to cause offense. Free speech is a double-edged sword, and an American near free-for-all free speech is a source of pride, but can cause issues for those who face abuse or humiliation at the hands of those using that right. The case will also have a knock-on effect in the Redskins litigation, undoubtedly clearing the path for the mark to remain registered. In the end, the Supreme Court seems to be completely right here, but this writer, being a proponent of a more limited free speech (although only for very narrow and specific exceptions), can't help but feel that this will pave the way for more offensive marks in the long term.